I am at an interesting stage in the writing of the Silent Eye’s April workshop. We are not up to production, yet. This early stage is about taking the initial ideas and coalescing them into a workable set of five dramas based on sacred temple principles. Each person attending the workshop plays a part; and the core themes are explored by (scripted) acting, forum discussions and personal exploration in the quiet of the lovely Derbyshire landscape.

One of my favourite themes, and one which always features in these workshops, is the notion of hazard. Our lives are full of hazard and yet we view it as a curse rather than a blessing. My eyes were opened to the constructive power of hazard many years ago, when I came across the works of John Bennett, one of the principle students of both Gurdjieff and Ouspensky in the middle years of the last century. Bennett spent the last twenty years of his life attempting to re-write the language in which the the ‘4th Way’ was couched. He said he did this as much for himself as for those who would follow, believing that time had moved on and that it was vital to encapsulate the vital essence of what Gurdjieff taught in a language that could be used for explanation with ‘modern’ people, from scientists to psychologists, but especially to the everyday women and men prepared to invest a little time in knowing why and how they had a large part to play in the creative flow of the universe and how the gates to that were opened by how they reacted to true hazard.

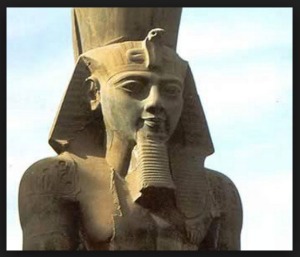

I was considering this, again, as I often do in January as the mental and emotional engine that powers the workshops needs to be cold-started. At the same time, I came across the use of the Greek word Ozymandias, the classical name for Rameses II, a figure that features in our workshop as the very driver of the ‘hazard’ that the participants need to live through.

The reference reminded me of the poem by the same name by Percy Shelley. I once learned this by heart for a presentation I was giving. The words are:

I met a traveler from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal these words appear:

“My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.