“It is what it is…”

I remember the evening Morgana said that to me, many years ago. We were in Glastonbury, doing the first of our year of bi-monthly talks.

The truth of it is profound. The sentiment behind the simple wisdom is how we resist what is…instead of embracing the new ‘world’ that has just revolved into view. The problem is like and dislike, of course, but that reaction is within us and nothing to do with the objective world that constantly reveals itself to the eye that watches from a different place…

It was the end of our weekend; Sunday morning – the last visit, and I wanted it to go well for all the Companions of the trip. Then the phone beeped. The text from Stuart said that half our party, travelling in the same car, were stuck on one of the roads leading to Lindisfarne, unable to overtake a large pack of cyclists who seemed unwilling to let traffic past.

“It is what it is…” I thought. Now what possibilities have just opened up?

We had a coffee, at a cafe that the others couldn’t miss on their way into the village, but, when it was going cold, gave up on Plan B and did some real-time adjustment. The issue with Lindisfarne is the tides… You only have so many hours to complete what you want to do before the sea returns and covers the causeway. There was a lot we wanted to do and only half a party. So, we did what anyone would do on a weekend named ‘Castles of the Mind’ – we went in search of our final one – castle, that is… We left a message with the others to meet up at the castle and set off…

From one perspective, I was dreading the first view of it. The last time I was here, and the time before, it was covered in scaffolding – the result of a complete refurbishment programme to weatherproof the exterior and restore the interior. As a result, once again, I had only been able to look at the workings, criss-crossed in its steel lattice.

But now, in the first of many wonderful surprises that the day was to contain, the castle that came into view as we emerged from the main street was wonderfully renewed…

And I started to smile, then laugh, as we made our way up the winding pathway to the high entrance… ‘Renewed’ – there it was: the key to the day, the gift to the symbolic Pilgrim, renewal at the end of a personal quest. What greater gift could there be?

The restoration work was a £3M project carried out by contractors on behalf of the National Trust. The castle has always been the main focus for visitors, though there are other very good reasons to visit this farthest part of the island. These include the headland itself – with an older and smaller mound nearer to the often wild sea; the lime kilns and the famous but often overlooked garden…

Visitors often assume that the whole history of the island is based on its religious past; but Lindisfarne’s intermediate history went far beyond its ancient holy status – though that religious link to a possibly more ‘vibrant’ and nature-facing Celtic Christianity is what attracts the thousand of pilgrims of all flavours who make their way to its shores. Monks don’t usually build castles – they build churches or monasteries. There was a monastery on Lindisfarne, too, and its ruins survive, today.

The history of Lindisfarne is written into the fabric of the castle, but we were not here to study history; but our own natures… It was therefore important to begin with what was there, now, before peeling back the layers of how it came to be so. In that, too, there was something symbolic to accompany our final footsteps.

The castle, with its restoration work complete, is a rather luxurious place – most unlike the typical castle. Thoughts of the previous day’s closing visit to the spartan Preston Pele Tower were fresh in our minds. There’s a good reason for this feeling of well-being: it was a luxury holiday home for a rich American publisher, Edward Hudson, from 1901 until the mid-1920s, and the restoration project has reinstated this look and feel. To accomplish this dramatic re-design of the building, Hudson used the services of a young architect and designer Edwin Lutyens, whose patron was the famous landscape gardener, Gertrude Jekyll. The latter contributed the planting scheme for the crags and added a small walled garden just North of the castle. Lutyens went on to become one of the most famous architects in British history.

The scheme for the work was to follow Lutyens’ plan to simplify the castle’s older structure by converting its interior into a great ’L’ shape. Rooms, doorways, fires and furniture were added, and a stream of well-heeled Edwardian visitors followed.

Sadly, the furniture is yet to be replaced and we were faced with a curious art installation, filling just about every room with wooden cubed frames, open on one side and – most of them – draped with coloured cloths. A poster explained that, as the furniture was still to be reinstated, the art ‘installation’ was deemed timely.

After much neglect, the castle was given to the National Trust by its third owner in 1944.

None of this is religious… To find the intersection between politics, power and religion, we need to go back to the time of Henry VIII, father of the future Queen Elizabeth I. Henry ‘dissolved’ the monastery of Lindisfarne in 1537. But such locations made useful coastal forts, particularly one so close to the troublesome Scots, and the last bastion of England – Berwick on Tweed. The result was that the island – and particularly the castle – became part of the Tudor military machine.

In 1543, France allied itself with Scotland. In response, King Henry mounted a military response designed to crush all such resistance to his rule. The military expedition was led by Edward Seymour, brother of Jane Seymour, one of Henry’s many wives. Seymour landed on Lindisfarne with ten ships and over 2,000 troops. This army set off from their temporary island base to punish the Scots… The campaign was brutal and achieved its goals. It was the last time that Lindisfarne was to play an important role in English military history, though Elizabeth I did order improvements and fortifications to the building. Coastal guns were deployed up to the 1880s, after which the castle was left to its decay until Edward Hudson found it and decided it would enhance his ‘English’ status…

But what about St Aidan, the man most associated with Lindisfarne – and the famous Lindisfarne illuminated Gospels. They belong to a much earlier time, a time when Celtic Christianity was spreading from Ireland via the Scottish Hebrides.

The man who would be St Aidan was born, on an unknown date, in Ireland. He is known as the apostle of Northumbria – the old name for the Kingdom of what is now Northumberland. Aidan was a monk on the island of Iona, in the Inner Hebrides, Scotland. King Oswald of Northumbria requested that a bishop be appointed to lead the conversion of his kingdom to Christianity (Celtic Christianity at that point) and Aidan was selected.

Aidan chose the island of Lindisfarne because of its proximity to the sea; the only way to travel, speedily, in an age where roads were tracks of rutted mud. Aidan was consecrated as Bishop of Lindisfarne in AD 635.

Aidan established his church and monastery within sight of our first location of the weekend – the royal castle of Bamburgh. Under Aidan’s direction, and that of his successors, particularly St Cuthbert, Lindisfarne flourished as a leading religious centre.

St Aidan died on 31st August 651, after a remarkable lifetime. It is ironic that Celtic (Ionan) Christianity travelled south and met Roman Christianity coming north. The latter was to win out at the Synod of Whitby, in AD 665, fourteen years after Aidan’s death.

Being next to the ocean had its downside, too, and in AD 793, the Vikings sacked the island, and the religious settlement was moved to Durham.

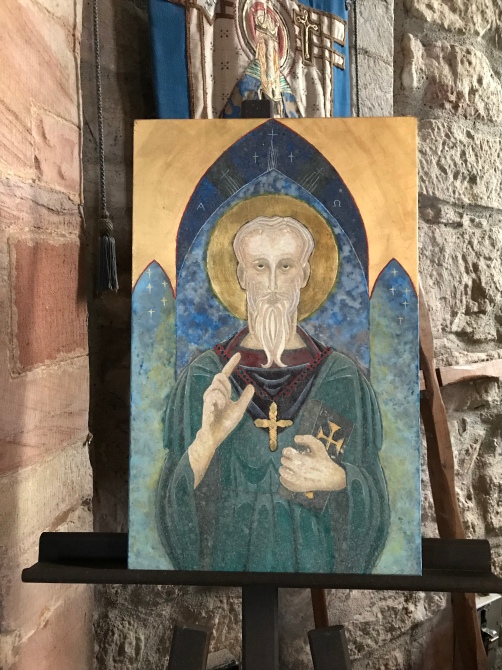

The story of St Aidan is well illustrated in the church of St Margaret, near the centre of Lindisfarne village.

We gathered here after a brief lunch, conscious that the tides were soon to encroach…

There is never enough time to see what Lindisfarne has to offer. Each time I go, I find new aspects to explore. We had to bring the Castles of the Mind weekend to a close. We were already running late and those attending had long journeys home.

Stuart knew of a small island, accessible at low to mid tide, which lay beyond the church. The simple wooden cross at its highest point marked the place of one of the original hermits. We picked our way across the wet beach and clambered up the rocks to see both cross and the view across to Bamburgh, our starting point.

It was perfect…

We conducted our last readings then held a silent meditation to mark the end of the weekend. Then we hugged and said our goodbyes.

Our journey as pilgrims was complete…

Interested in the next Silent Eye weekend?

Full Circle? – Finding the way home…

Penrith, Cumbria

Friday 7th – Sunday 9th December, 2018

End of Castle of the Mind

©️Stephen Tanham

Other parts of this series:

Part One, Part Two, Part Three, Part Four, Part Five.

Stephen Tanham is a director of the Silent Eye School of Consciousness, a not-for-profit organisation that helps people find a personal path to a deeper place within their internal and external lives.

The Silent Eye provides home-based, practical courses which are low-cost and personally supervised. The course materials and corresponding supervision are provided month by month without further commitment.

Steve’s personal blog, Sun in Gemini, is at stevetanham.wordpress.com.

You’ll find friends, poetry, literature and photography there…and some great guest posts on related topics.

Reblogged this on Jordy’s Streamings.

Thank you, Jordis.

Glorious Steve, thank you for this rich history and recap of your pilgrims journey!💗

We missed you, Jordis. Come back, soon x

Thank you, Steve! I remember when we were considering whether I could make it to join all of you but I had my dates wrong. But alas would have cried the entire time as I always seem do when visiting holy sites. Can’t wait for April!

🤗

Thank you, Sue x

Reblogged this on Where Genres Collide and commented:

More interesting history!

Thank you, Tracie – and for the reblog 😀

You’re welcome, Steve!